If fruits, by definition, are the tasty mechanism for a plant to spread its seeds, how then, does Mother Nature allow such a thing as seedless fruit? After all, plants with seedless fruits are technically sterile. The short answer is, she doesn’t…that is, unless a fruit-bearing plant produces them by chance through a mutation. And this, my friends, is where the story gets interesting.

To take a step waaay back, the meticulous art of plant breeding to produce desired traits has been going on for a very long time. Characteristics like fruit size, sweetness, flavor, skin thickness, and residence to disease have been tweaked by humans through natural breeding methods. Propagation through grafting and cuttings is another ancient technique — a quick and reliable means of reproducing plants so that they are genetically identical to the parent plant. In fact, most fruit trees today are grafted onto rootstock, combining the best characteristics of both plants.

Many seedless fruits result from a genetic mutation that, once discovered, can be propagated through grafting or cuttings.

Take seedless grapes as an example. A genetic mutation prevents the seeds inside these grapes from forming completely, leaving nothing but tiny specks. The seedless grape is thought to date back to Ancient Rome and was first introduced to the U.S. in the mid-1870s under the name Thompson, after the Scottish immigrant who first cultivated it for raisin production. Most seedless grapes today derive, at least in part, from the Thompson variety.

The navel orange, as another example, comes from a single branch on a tree that was discovered in the early 1800s on a plantation in Bahia, Brazil. The fruits on this branch were seed-free and had a “navel” — a tiny second orange that grew in from the blossom end of the main fruit. These sweet, easy-to-peel, and seedless navel oranges were propagated through grafting and beloved by many. By the late 1800s, navel oranges were grown commercially in Southern California and remain one of the most popular citrus fruits today.

This brings us to watermelon, where the process of producing its seedless counterpart is even more complicated. Seedless fruits can’t produce on their own and watermelon vines can’t be easily grafted to form new plants. So how, then, can one produce a watermelon that offers the convenience of having few or no hard black seeds? This is the puzzle that Dr. O.J. Eigsti set out to solve back in the 1950s.

Eigsti, a plant geneticist from Goshen, IN, pursued a chemical process that doubled the number of chromosomes in a normal watermelon plant. The idea was that if this “tetraploid” watermelon is pollinated by a normal watermelon plant, the resulting fruit would be sterile (seedless) with three sets of chromosomes (“triploids”).

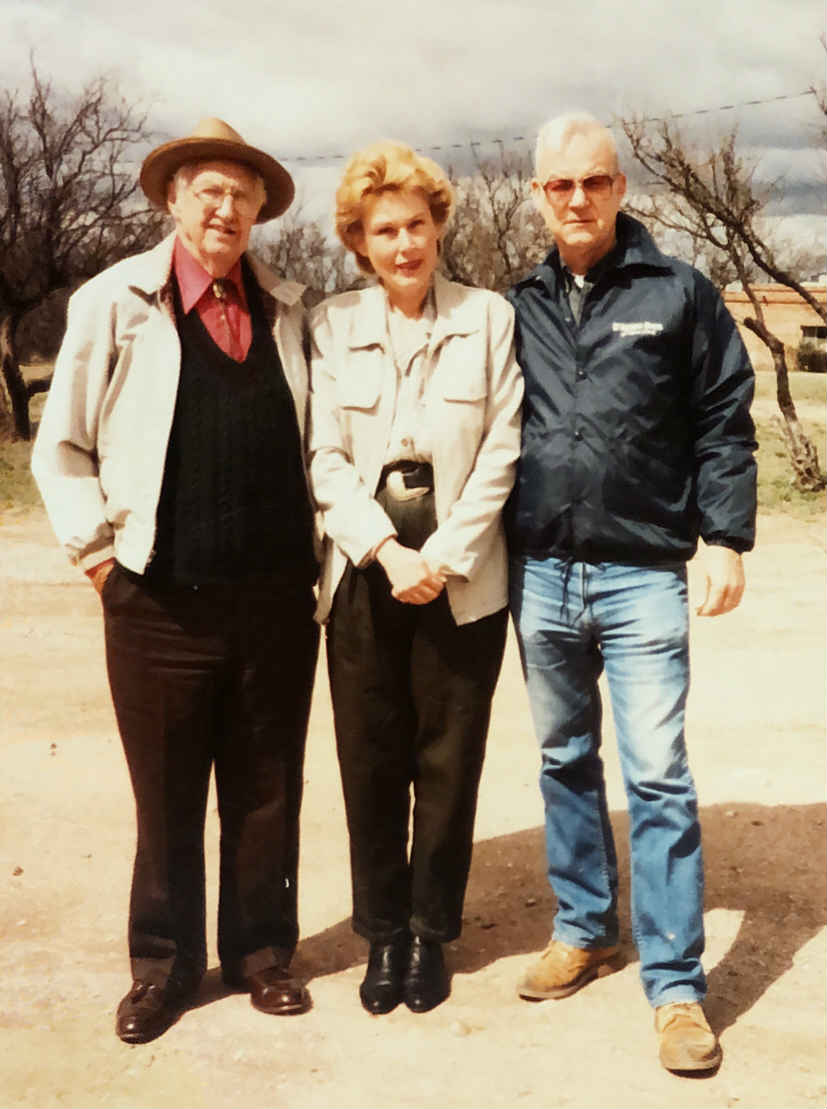

Clearly, Dr. Eigsti was onto something, but it took him a while to find commercial partners. Introducing something new to the market is risky business! Eventually he entered into a partnership with a seed company and found a grower to trial the seedless variety. Of all people, the grower was the grandfather of our very own Lesley! The rest is history — today, it would be difficult to find anything other than a seedless watermelon in commercial markets.

The late Dr. Eigsti (left) with Lesley’s late grandfather and grandmother, Robert and Kay Shipley, circa 1992.

Seed companies charge a premium for these seedless “triploid” varieties. Growers plant them alongside seeded watermelons, which provide the pollen needed for bees to pollinate the flowers on the seedless variety. Visit any farm and you’ll see this at play: two rows of seedless for every one row of seeded.

Scientists today are pushing the envelope when it comes to new varieties of seedless fruits. Even so, the process remains tedious — researchers may look at thousands of plants before locating the perfect fruit that is not only attractive to consumers but also to growers. So the next time you enjoy one of these fruits, consider taking a moment to appreciate the long history — and the tedious science — behind it 🙂